On Election Day, South Carolina Banned 7 Books from Schools

Following Utah's lead, South Carolina is engaging in state-sponsored censorship

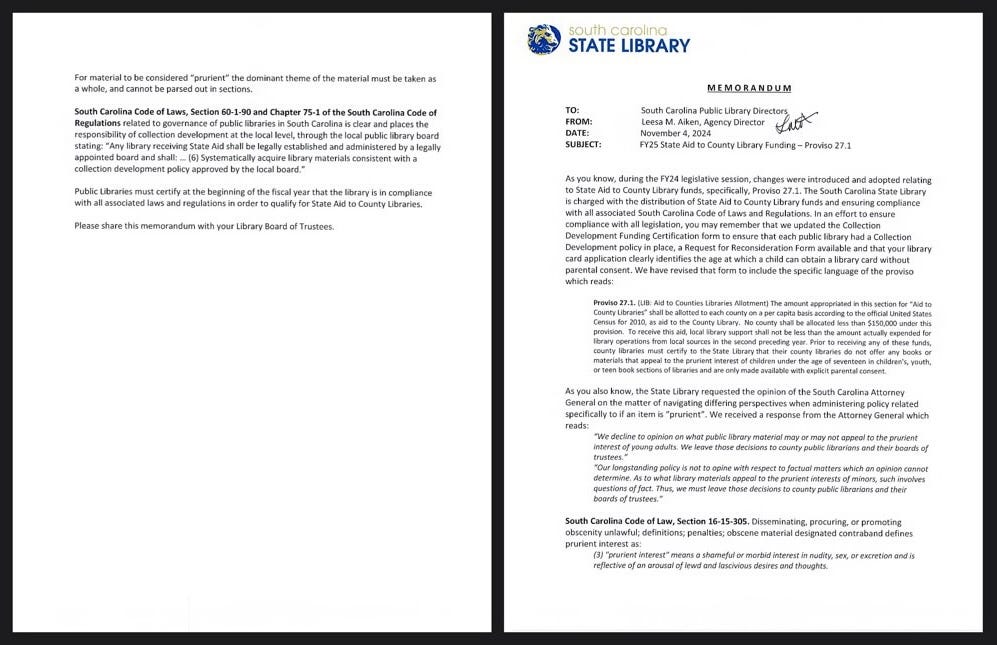

Earlier this year, South Carolina passed two pieces of vague legislation aimed squarely at libraries across the state. The first was a proviso in the state budget. Though budget allocations for public libraries were now increased for the first time in recent memory, there were strings attached. Every public library now has to “certify to the State library that their county libraries do not offer any books or materials that appeal to the prurient interest of children under the age of seventeen in children’s, youth, or teen book sections of libraries and are only made available with explicit parental consent.” That proviso, of course, had no definition for “prurient interests.”

The South Carolina State Library is now tasked with tracking public library compliance, despite the fact that public libraries are governed by local boards and this, by definition, removes the so-called local control this kind of proviso exists to enshrine. The State Library has no power over collection policies in libraries across the state. What books that appeal to the “prurient interests” of children is up to the state’s Attorney General.

That information, pictured below, was shared this week with libraries across the state. It is as conveniently vague as you’d imagine.

The second piece of legislation passed in South Carolina, Regulation 43-170 (R-43-170), impacts schools and specifically, school libraries. Decisions over content in libraries was placed in the hands of the South Carolina Department of Education, headed by Ellen Weaver. R-43-170 provides that the Department will create a two-prong test for public school boards to use in determining whether or not materials are appropriate for students 17 and younger. The first prong is that the material is age and developmentally appropriate. The second prong is that materials in schools align with state educational instructional programs. R-43-170 would create a uniform process for school board trustees to use when a book complaint is filed and sets up an appeal process through the SC Department of Education, whose decision on any given book would apply to books statewide. This provision is similar to the recent Utah bill which bans books in every state school if it is banned in at least three districts–so it is of zero surprise that South Carolina created its first official state-sanctioned book ban list this week.

Weaver used an array of underhanded tactics to push this deeply unpopular bill through. One included using taxpayer dollars to hire Miles Coleman, attorney and president of the Columbia chapter of the Federalist Society, an organization that supports conservative and libertarian lawyers, to show up to department meetings about the legislation in support of it.

As I reported this summer at Book Riot with information obtained from the ACLU of South Carolina:

Weaver authorized up to $25,000 in taxpayer money to have Coleman show up to State Board of Education meetings in support of R-43-170 on her behalf. He is not an employee of the Department of Education but he, like Weaver, is a graduate of the fundamentalist Bob Jones University. He was hired by Weaver specifically to advocate for this censorship bill and protect the department from potential litigation–almost as if it was clear from the start that this was not only an unpopular bill and one rooted in fundamental doctrine but also a potential violation of the First Amendment.

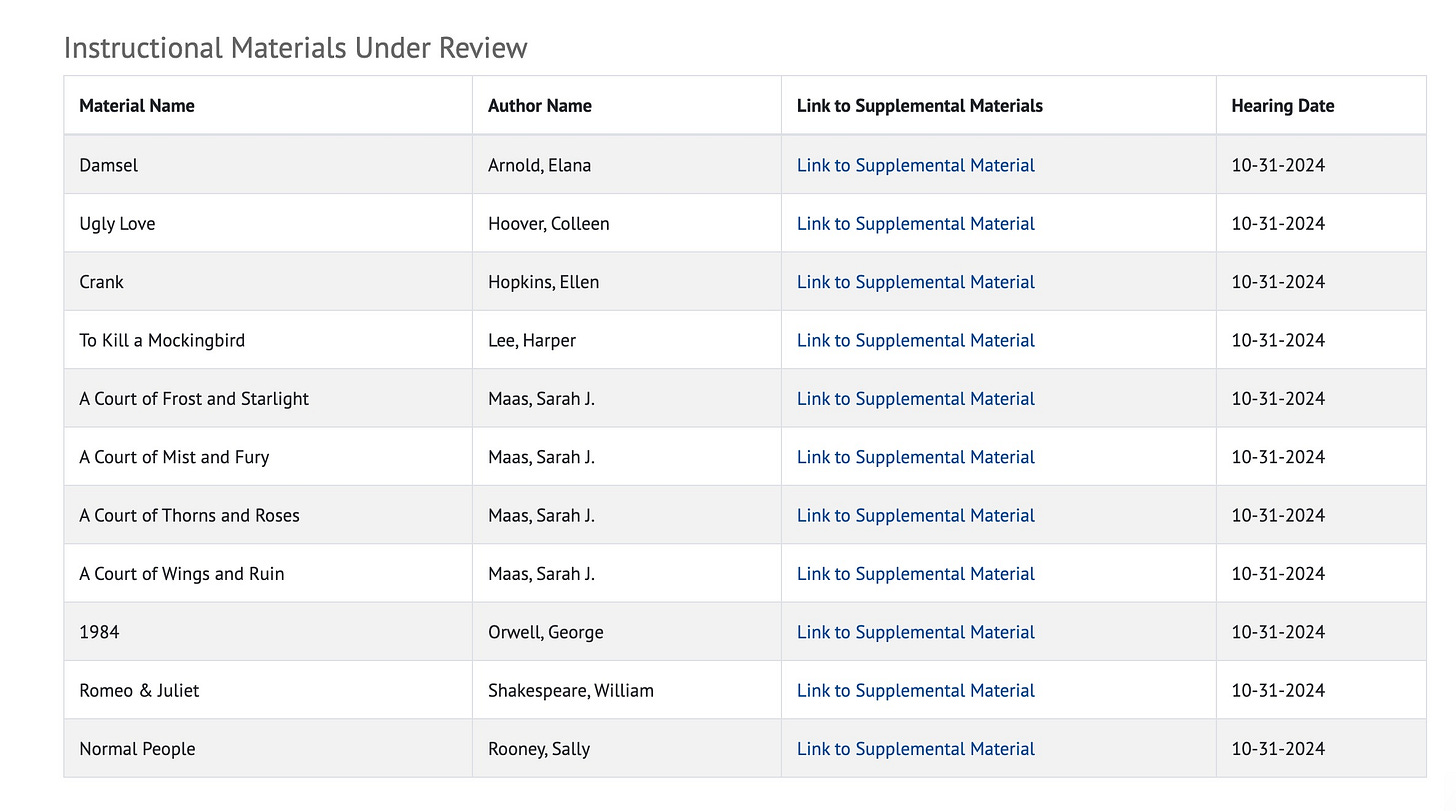

On October 31, the State Department of Education’s Instructional Materials Review Committee (IMRC) held their first meeting to discuss books they will or will not allow in schools across the state. The committee, comprised of five older individuals, four of whom were white, met to discuss the future of 11 books in schools across the state. It was the first official meeting of the IMRC, whose duty now is to establish the second prong of R-43-170. These were the 11 books they evaluated and discussed:

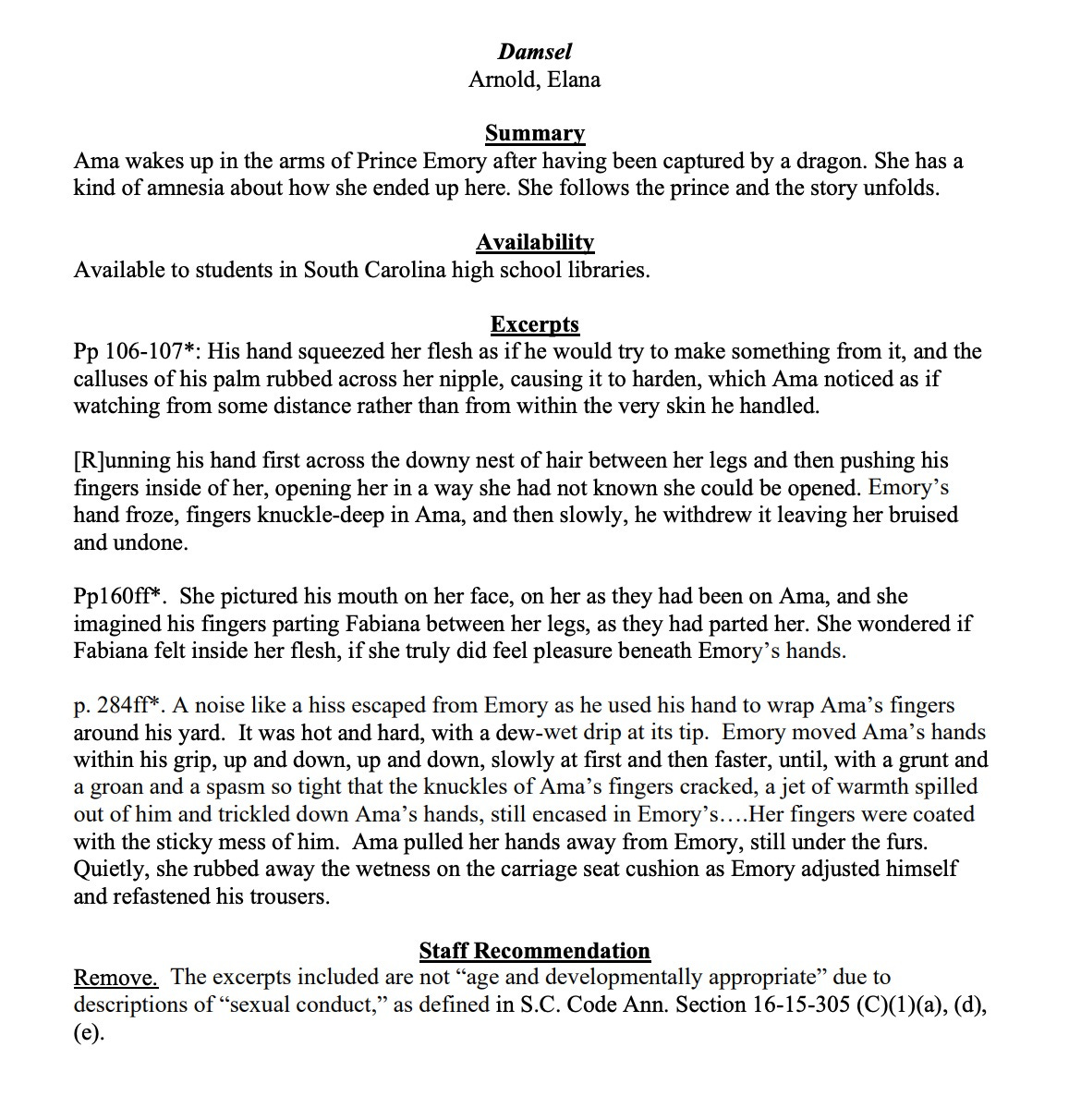

You can look through the supplemental material for each title here. As you’ll see, those documents are little more than cherry-picked passages–a la BookLooks–that do not rise to the legal Miller Test definition of “obscenity.” Along with the short passages that the committee looked to be titillated by, they made determinations about those titles. Below is the report for Damsel.

Note that the staff recommendation–nor the law itself–mention the Miller Test. Instead, “age and developmentally appropriate,” a vague and meaningless phrase that can apply anywhere.

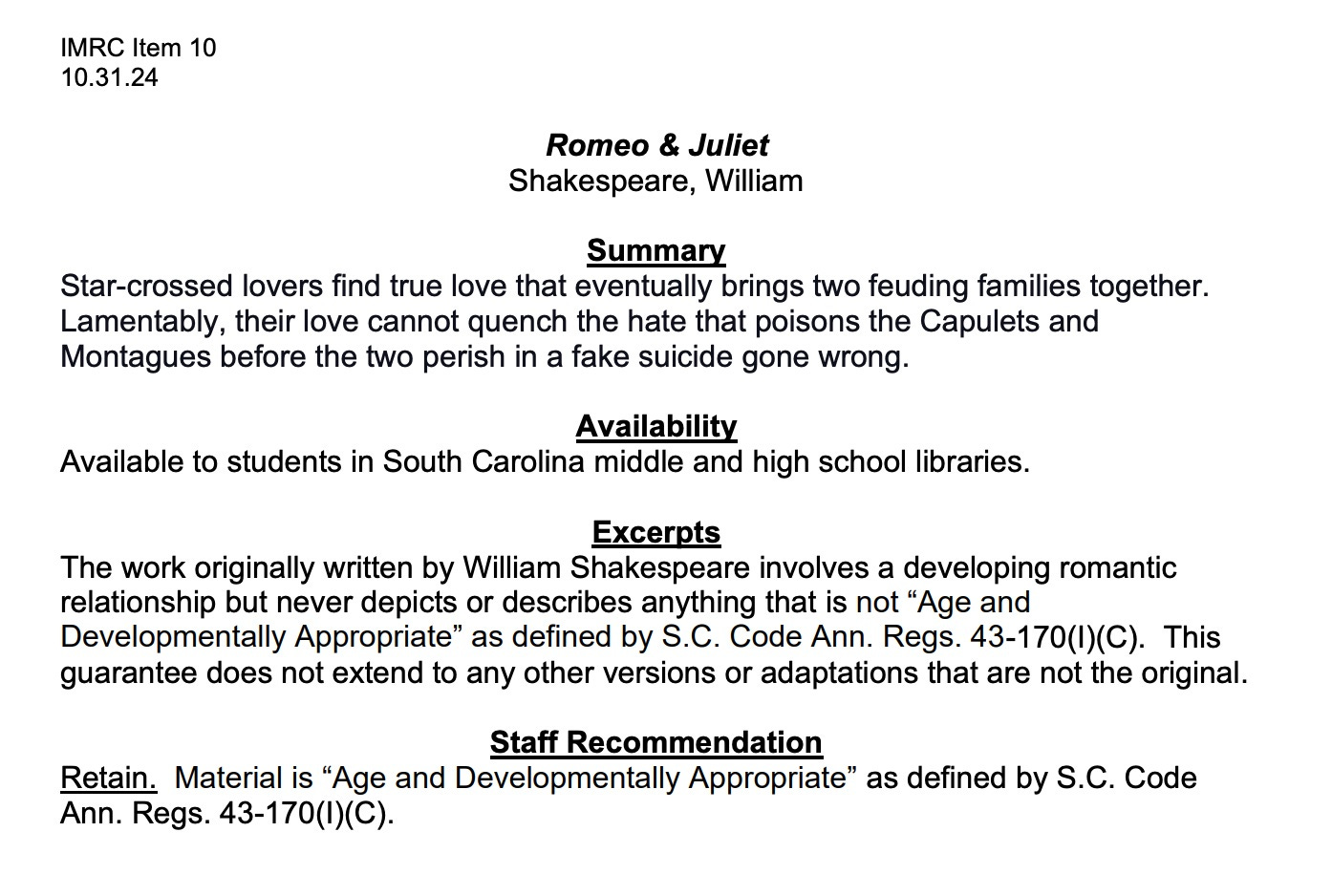

Alternately, among those 11 books were a few literary classics that, well, didn’t have the same kind of pick and choose technology at play. Here’s the report for Romeo & Juliet.

The IMRC recommended removing all of the titles under review except for Romeo & Juliet, To Kill A Mockingbird, and 1984.

South Carolina’s chapter of the ACLU recorded the Halloween meeting. There was little discussion of the books on the agenda, and it appeared many on the committee may not have bothered reading or reviewing the books at all. That’s easy to do when you can cherry pick your proof of anything. The meeting was recorded and can be viewed here.

On Tuesday, November 5–yes, election day–on the State Board of Education consent agenda was the work done by the IMRC. Several professionals in education, literacy, library work, and more showed up to speak during the public comments. But those public comments fell on disinterested, agenda-pursing ears. One mentioned that she was gravely concerned about the state banning AP African American Studies and its decision to infiltrate public education with biased, non-factual materials from PragerU. Current and former classroom teachers in the state called this process nothing short of absurd.

Unlike in Utah, where the state sanctioned book bans begin with school district decisions, that’s not the case in South Carolina. This came up in the meeting, as it is the IMRC and State Board of Education making determinations on books that are or are not appropriate in schools–not the schools themselves. That “local control” so beloved in arguments about book censorship has zero basis in the policy; indeed, at least with Utah’s draconian policy, the origin of challenged books can be traced.

Not so in South Carolina. In South Carolina, parents may initiate a complaint to the state if they don’t like the results they get in their district but the State Board of Education has also granted itself power to pick and choose what they do and do not want to review. From their policy:

Any Complainant who is aggrieved by a decision of the district board may file a written appeal to the State Board of Education (“State Board”) within 30 days after the district board announces its decision in a public meeting. The Complainant shall file the appeal by completing and submitting a Notice of Appeal of Instructional Material promulgated by the State Board and made available on the State Board’s webpage. The Complaint shall submit the completed Notice of Appeal of Instructional Material to the committee’s scheduling coordinator through email or mail. In addition, the State Board may, of its own volition and on its own initiative, make determinations in the first instance regarding the educational suitability or the Age or Developmental Appropriateness of specific Instructional Materials pursuant to the criteria and requirements set out in Regulation 43-170.

So on election day, when the state and country were worrying about or gleefully voting in favor of impending fascism, the State Board of Education continued forward and banned the first books in the state. The following books are not allowed in any public school in the state. Emphasis is important here because these books are perfectly fine in private schools in the state.

Damsel by Elana K. Arnold (Read Elana’s letter about her book facing a state ban)

Ugly Love by Colleen Hoover

A Court of Frost and Starlight by Sarah J. Maas

A Court of Mist and Fury by Sarah J. Maas

A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J Maas

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Four of these books appear on the Utah state sponsored book ban list, too.

Ellen Hopkins’s Crank is not out of the woods. The 20-year-old book is among the near three dozen titles banned in 50 or more school districts nationwide. The State Board of Education in yesterday’s meeting postponed their decision, but given that the IMRC recommended its banning, it’s likely not going to be on school shelves much longer, either.

Take a moment and read this again. We now have the second state in the country creating a list of books absolutely, positively banned from any and all public schools within its boundaries. Whether or not you agree with teenagers reading Hoover or Maas or Rooney, all of those books feature older teens and young adults. Whether or not you agree with teenagers reading Hoover or Maas or Rooney actually doesn’t matter one damn bit–if those books are selected and purchased for a public school facility, that is because a trained professional used their experience, knowledge, and tools to make that educated decision based on their community.

No one is reading these books for school assignments. They may, however, be reading them to understand what it is to navigate an uncertain world full of confusion, mixed messages, and yes, sometimes unconventional sex!, in a safe environment of a book.

But none of that matters when you can boil down 400, 500, or 600 pages into seven passages from the book that you Googled instead of read. Because what’s the point of being in charge of an education system if you can’t simply wield your power and weird, unhinged fixation on sex rather than showcase your ability to be a leader in overseeing actual learning.

Keep your eyes on South Carolina as they continue to review books and ban them. The IMRC is supposed to keep their list and their meeting agendas public, as is the State Board of Education. It appears that when the IMRC has made some choices, the following full board meeting will be where those recommendations are simply placed on a consent agenda.

They did this on election day because they knew they could do this on election day, and it’s not going to get better from here.