The Pro-Censorship, Anti-Library Bills Already Filed for 2025

Killing the Department of Education is one we already saw coming.

Mike Rounds, a South Dakota Senator, officially proposed the bill to do precisely what the new administration promised–aided by Project 2025 and years of campaigning by anti-education activists, including Moms For Liberty and their ilk. That is to defund the Department of Education. Whether or not the job will get done is debatable. If it passes and we see the end of the Department of Education in favor of handing educational responsibility to the states, then we’re going to see states that have an educated population right next door to states that have a religiously indoctrinated one. That’s if the latter is even possible.

So many of the very people who are advocating for the end of the Department are the same ones in “parents rights” groups talking about how difficult getting accommodations for their child is. Somehow, they think this will make it better.*

But this is far from the only concerning bill related to the future of books, reading, and libraries in the United States. Last year’s legislative session brought a number of draconian laws passed across so many states. Two of them, one in South Carolina and one in Utah, have given the state the power to ban books across every public school if they deem it so appropriate. This is state-sanctioned censorship, both of the Capital C kind and the lowercase c kind. Idaho gave parents the power to sue public libraries if their (unfounded) demands about inappropriate materials available for those under 18 aren’t addressed quickly enough. We saw laws in Tennessee and elsewhere go into effect that have led to books being pulled from school shelves by the hundreds. It is unclear whether or not Tennessee will follow their peers in Utah and South Dakota and develop a state-sanctioned ban list, but they have already told Knox County Schools what books need to be removed and, unfortunately, no one has formally challenged any of the book ban decrees they’ve made.

Emboldened by all of these laws, we’re not only going to see repeat efforts emerge. We’re also going to see more and more new bills pop up. It is a nonstop game of whack-a-mole.

Find here are several concerning bills already pre-filed for the 2025 legislative sessions across the country.

Alabama

SB 6, filed by Senator Chris Elliot

While library board members in Alabama are appointed by either their city or county council members, this new bill would give those same councils the power to fire board members by a mere two-thirds vote. This means that library board members that do not behave at the behest of their city or county council–as opposed to the whole of the communities they are to serve–could be fired at the whim of those councils.

This is what started to take shape in Prattville Public Library and has led to fights between the small vocal minority of people aligned with both Clean Up Alabama and the local Moms For Liberty and pro-library champions such as Read Freely Alabama.

Imagine this: the city council is hearing complaints from Clean Up Alabama members about pornography they believe is in the library (reminder: there’s never pornography in the library). The group members weren’t making their case strongly enough at the library board, so now Clean Up folks go to city council, who is either tired of hearing about it or who are conveniently aligned with the Clean Up crew, since their roles on council are at stake if they don’t capitulate to said group.

You’ll notice nothing in this bill about library board members engaged in wrong doing. That’s not necessary. They can be fired whenever the city or council wants to fire them.

It’s bad faith all the way down.

HB 4, filed by Arnold Mooney

Mooney was so excited to criminalize librarians in the state that he prefiled this bill for 2025 back in July. Simply having certain materials in libraries would be enough for librarians in those institutions to be charged as sex offenders. This would apply both in public schools and in public libraries.

The bill elucidates what is meant by “sexual conduct” and who can be charged for merely having or displaying such materials. That would be the part that’s explicitly applicable to libraries. Here are some of the concerning bits:

In K-12 public schools or public libraries where minors are expected and known to be present without parental presence or consent, any sexual or gender-oriented conduct, presentation, or activity that knowingly exposes a minor to a person who is dressed in sexually revealing, exaggerated, or provocative clothing or costumes, who is stripping, or who is engaged in lewd or lascivious dancing.

“Any sexual or gender-oriented conduct” is purposefully vague. The intention and way it will be interpreted is exactly as you’re likely thinking: anything with LGBTQ+ content, whether it’s a book about what those letters mean or what consent means or a book where a character is depicted wearing clothes that politicians do not believe aligns with the gender of that character or anything else. And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richards and Peter Parnell is an actual factual picture book about two male penguins in the Central Park Zoo who raise an egg together, but it has been under fire in place after place after place because actual factual grown ups think it falls on the inappropriate side of “sexual or gender-oriented conduct.” Who needs facts when you have politicians to decide what truth means?

The granularity and fascination with specific sexual acts, behaviors, or appearances tells you more about those who’ve drafted this legislation over the years than it does whatever it is they’re seeking to punish.

HB4 ultimately operates a lot like the draconian bill targeting public libraries in Idaho, though in Alabama, it would apply to both public and school libraries. Anyone who wants to cry pornography can, and the library has to waste its time and resources to respond immediately or face criminalization.

Naturally, as in all bills of this flavor, there are not actual repercussions laid out. That gives the state plenty of flexibility to decide whether or not a librarian whose collection has, say, The Hips on the Drag Queen Go Swish, Swish, Swish, should be issued a misdemeanor or felony.

HB 67, filed by Scott Stadthagen

Speaking of drag queens, see yet another anti-LGBTQ+ piece of legislation prefiled in Alabama. This bill, in essence, outlaws queer people being visibly queer from public spaces. In addition to legislating who can use what bathroom, HB 67 would ban drag performances from all K-12 schools and public libraries in the presence of minors without explicit parental consent.

The obsession with what is under someone’s pants by so-called adult professionals with power is deeply disturbing.

From the bill:

BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF ALABAMA:

Section 1. For the purposes of this act, the following terms have the following meanings:

(1) DRAG PERFORMANCE. A performance in which a performer exhibits a sex identity that is different from the sex assigned to the performer at birth using clothing, makeup, or other physical markers.

(2) SEX. The state of being male or female as observed or clinically verified at birth.

“Clinically verified?”

Would someone who has polycystic ovarian syndrome like myself be banned from being in public giving any kind of performance because I display some “physical markers” that are not aligned with my having a vagina, such as hirsutism? Does it mean that no books can be read by a librarian who chooses to dress up as a character in the book if that character does not align with their genitalia?

What’s at stake is the safety of visibly queer people. But a consequence of that is, once again, an ill-defined set of ideas that ultimately target anyone that does not conform to them.

Ohio

HB 556, Filed by Adam Mathews

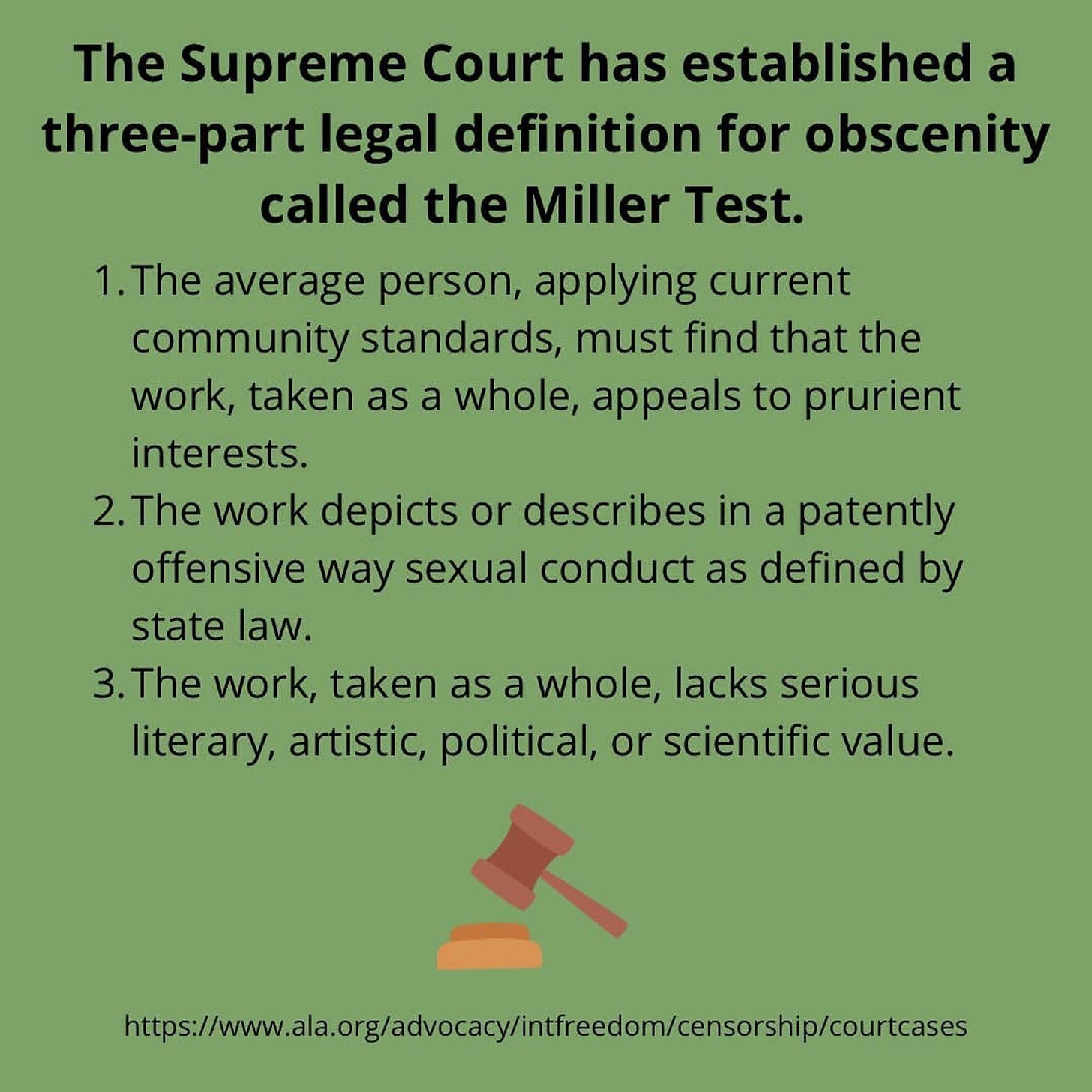

Like colleagues in other states, legislators in Ohio believe they should pursue criminalization of library workers and educators for “pandering obscenity.” This law would remove library workers from being protected for having certain materials in their collections–but as you’ll recall, library workers and educators do not have, nor do they pander, anything considered obscene under the prevailing test for obscenity, the Miller Test.

The law won’t matter. This will, like all of these bills, be interpreted in whatever way is most beneficial to the far right; see this recent piece from the ACLU on the government’s inability to define pornography and its insistence on prosecution of it. The penalty for violating HB 566 a fifth degree felony.**

Here’s a scenario that could play out. The public library has a collection of books about puberty in the youth nonfiction section. This is the audience for whom the books are written and thus, they’re in the appropriate area of the library. An aggrieved parent or individual with a particular agenda could file a complaint that those books are in the sight lines of young people and because some of the books include images of human anatomy, they claim the material is obscene.***

The state not caring about nuance when it comes to obscenity, thanks to a stacking of the system with those who have a specific political agenda, will ignore the Miller Test. It will pursue prosecution of the library workers responsible for such material being peddled in the library. That’s a bonus paycheck for police, too.

Sure, those library workers could sue. But what library workers make enough money to do that, let alone when they’ve just been accused and charged for a felony? Even if the money is there and the case is solid, lawsuits take months, if not years, to move through the system.

By then, the reputations of these individuals who were simply doing their job are sullied.

HB 622, filed by Al Cutrona

Conveniently, this bill would allow such a scenario as the one mentioned above to play out without any real challenge. HB 622 would require every library board in the state to create a policy that decrees no material deemed “harmful to minors” would be on display in the public library. If a library fails to comply with this, they would lose funding–that funding would be “redistributed.”

Don’t worry. “Harmful to minors” isn’t well defined, so it can be interpreted at will. For libraries, the state has gone the distance to offer a variety of ways that material can be hidden from anyone under the age of 18 right in the bill:

(C) A library may comply with the requirement in division (A)(2) of this section by doing any of the following with respect to material that is harmful to juveniles:

(1) Placing the material behind blinder racks or similar devices that cover at least the lower two-thirds of the material;

(2) Wrapping the material;

(3) Placing the material behind a circulation counter;

(4) Otherwise covering the material or locating it so that the portion that is harmful to juveniles is not open to the view of juveniles.

Every single one of these examples is censorship. Every single one of these flies in the face of the responsibilities, purpose, and ethics of librarianship.

One of the biggest arguments made throughout this ongoing anti-library and anti-book crusade since 2020 is that communities need to have more “local control” with their public schools and libraries. And yet, bills like this one take that local control away because none of this was ever about local control. It was about control, period.

You see, with HB 622, anyone in the state can file a complaint about any library they believe is out of compliance. It’s not cardholders to the library. It’s not taxpayers to the library. It’s anyone in Ohio. The responsibility of determining whether or not libraries are in compliance then falls on the State Library Board.

And who appoints members of the State Library Board? It’s the Director of the Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, who is themselves appointed by the state governor. If the Director wants to keep their job, they’ll listen to what the governor says about whether or not a library is in compliance with this law.

About that redistribution of funds: for each month that the library is deemed out of compliance with the law, their funding will be distributed to other public institutions locally. That means people won’t get paid for their work some months, and it means that libraries will not have budgets to pay their bills, acquire materials, or run programming. It also purposefully pits the public library against other municipal goods and services.

You can see where this is going.

(B) A county treasurer that has received a report described in division (D)(1) of section 3375.68 of the Revised Code shall not make the monthly payments otherwise required under division (A) of this section to the board of public library trustees of a library that is the subject of that notice, beginning with the next required payment. Instead, the county treasurer shall distribute any such payments among the other boards of public library trustees, the county, and the municipal corporations and boards of township park commissioners fixed an allocation from the county public library fund. The amount allocated to each board or subdivision shall equal the amount of the forgone payment multiplied by a fraction, the numerator of which is the amount of the board's or subdivision's allocation for the applicable month, not accounting for any adjustment required by this division, and the denominator of which is the sum of the allocations of all such boards or subdivisions for that month, not accounting for any adjustment required by this division.

This reallocation of funds will continue until a report is filed that the library is no longer displaying the so-called “inappropriate” material.

Ohio legislators are simply gearing up to put a bounty on library workers between these two bills if they don’t drain the organizations of all their funds first.

Texas

There are several bills in Texas that should be raising a lot more concern than they are, and that’s by design. Flood the legislature with a lot of similar-sounding ideas and you begin to lose people who are trying to keep up.

But rather than lay them out, this is where we turn to folks like Frank Strong, who have developed a guide to these terrible bills. Here’s what those bills are and why they should be raising concerns.

I’ll also add that the new Christian-focused curriculum passed by the state, while not required to be implemented in schools, offers a pretty enticing incentive for districts struggling to stay solvent: $40 a pupil! As I wrote in the first look at 2025 censorship trends:

It’s also extremely convenient leverage for the voucher program: if you don’t like your public school teaching Christian-infused curriculum, then you should support a voucher program which allows you to send your kid to any school in the state. If you’re a school and worried about how cash-strapped you’d be because of the voucher program, then you have a solution in implementing this curriculum that the state will pay you to implement.

Problem, meet solution.

Perhaps it is worth addressing here, too, that this new curriculum is not only problematic as hell for its Christian basis—separation of church and state doesn’t actually matter to politicians who see the issue not as keeping the church out of the state but instead, keeping the state out of the church—but it further lines the pockets of right-wing politicians. Many of the lessons that the Texas State Education Department passed come from Mike Huckabee’s media company.

Despite not being the leader on vouchers, we need to remember that as goes Texas, so goes the nation. Texas isn’t red because of it being filled with people who support the far right or even the centerist GOP. It’s red because of decades of gerrymandering, voter suppression, and voter disenfranchisement.

So go those in states who follow the Texas lead.

Although the goal here is to highlight the not-great library and book ban bills on the docket for 2025, I don’t want to ignore the opportunities out there for those who are in states with good bills on tap already. If you see your state here, contact your representative/senator and push for these bills to proceed. Get into the ears of the people who work on your behalf. They may not listen, but you create a necessary paper trail and strengthen a muscle in your civic engagement tool kit.

I’ve tried to be realistic, and if it comes off pessimistic, that’s because the reality is such. But that does not in any way mean these are not worth fighting for. It means that the folks behind these bills are library allies–in some cases, that might be surprising–and they are worth building communication and alliances with as best as possible.

Arkansas

HB1028, Filed by Andrew Collins

Anti-book ban bills have value, even if that value is more symbolic than actual (more on that in next week’s Literary Activism column). There really are two types of these bills. The first shores up protections of library workers in the fight to keep books on shelves and the second ties a small incentive to updating and implementing anti-book ban policies into the library. Some bills do do both, but states which have passed either type of bill did so knowing what would pass without the least fuss in their legislature. Small successes matter.

Arkansas has introduced legislation that mirrors Illinois’s anti-book ban bill. It ties a small pool of money to anti-book ban policies in libraries state wide. HB1028 begins by completely repealing Arkansas Code § 5-27-212, then provides criminal protections for library workers and school employees when claims are made that they have provided “obscene material.” This is the opposite of what Ohio HB556 wants to do.

When you pause with that, you recognize what an absolute farce all of this is.

HB1028 is a lot of red lining. But between those lines is the essence: libraries need to have a collection development policy that explains that they do not participate in banning books based on partisan or doctrinal belief. Libraries which do that are then able to apply for money from the State Library.

This won’t end book bans. We’ve seen in the last couple of weeks that Illinois’s model legislation doesn’t mean every school or library will bother to participate for the extra cash. But for many districts that do take part, that small pool of money can make a huge difference. At the Association of Illinois School Library Educators last month, I asked attendees what kind of dollar amounts they were seeing. It’s based on population served, but the average was between $800 and $1500 per building covered by the anti-book ban policies. That’s not insignificant money for most libraries, especially small ones where it makes the difference between replacing completely destroyed items or taping them back together with a lick and a promise.

Whether or not this bill passes, a crucial takeaway here is that there is at least one member of state legislature who is listening to library concerns and taking them seriously.

Michigan

HB6034, introduced by Veronica Paiz

Speaking of anti-book ban bills, here’s Michigan’s filing of a public library freedom to read act in the state. I had the opportunity to view this one nearly a year ago, and I’m thrilled to see it has been officially filed. Note that this bill is specific to public libraries, unlike bills in Illinois, Michigan, and other states that apply to both public libraries and public school libraries.+

This bill requires every public library to have a collection development policy that addresses the entire life cycle of all materials in its collection. In other words, how materials are selected and who selects them, as well as who can weed materials and what criteria are used to make those decisions. Crucially, every library must have a process for how materials can be challenged by the public–remember that the right to speech and the right to petition should be upheld in public libraries, too. The policy needs to also outline when, where, and how such reconsideration requests are approached. Not every complaint will be met with a formal review.

Addressed in HB6034 is this: the individual lodging the challenge needs to have read or reviewed the entire material and they must be a resident of the library’s service area. Again, notice how that differs from Ohio’s proposed bill where anyone in the state can start to hunt down library workers complain about library material.

Further:

(2) A reason or basis for a request for reconsideration cannot be made based on the religion, race, color, national origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, height, weight, familial status, or marital status of the author or because the subject matter, content, or viewpoint of the material involves religion, race, color, national origin, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, height, weight, familial status, or marital status. The director or, if there is no director, the chief executive employee working at the public library has discretion to determine if the reasons stated in a request for reconsideration comply with this subsection.

(3) A public library shall not grant a request for reconsideration based on the subject matter, content, or viewpoint of material, unless the material has been adjudicated to be obscene or otherwise unprotected by the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States or by section 5 of article I of the state constitution of 1963, as determined by a court of competent jurisdiction over the community in which the public library serves.

HB6035, introduced by Carol Glanville

This legislation is the same as above, but it is applicable to district libraries throughout the state of Michigan.

Missouri

HB95, Filed by Anthony Ealy

Of the three anti-book ban bills already on the docket for 2025, this one has the least likelihood of passing. Missouri has been one of the first in the wave of significant book banning and the red-heavy legislature doesn’t suggest there’s a lot of promise for change.

Despite that, it needs to be talked about and it is necessary to advocate for it to your representatives.

Ealy’s bill would ban book bans at publicly funded libraries. No materials getting state money could ban materials based on political or doctrinal beliefs. The only other component of the bill as submitted is that libraries with state funding are not required to purchase any particular materials. In essence, books can’t be banned based on politics and the library isn’t required to purchase anything based on politics. This needs to be fleshed out much more but it does create an interesting separation between the state’s responsibility as it relates to public libraries and vice versa.

SB159, filed by Mike Henderson

Yet another take on the anti-book ban bill, this time from a republican in the Missouri Senate. This particular bill requires that public and public school libraries have a challenge policy and that those who file challenges must sign an affidavit that says they read and reviewed the material in full and that they are a resident within the taxing body of that institution.

The bill strengthens the protections for library workers who defend materials kept in the library as well.

This part is especially interesting:

Digital library materials that undergo reconsideration shall be subject to removal or restricted access at the title, issue, and article level. Any third party contracted to provide databases that contain or provide access to digital library materials shall have the ability to curate those materials using a mechanism that allows for the removal or restriction of access to challenged content without disrupting access to the remainder of digital library materials accessible in the public library or school library. Curation of digital library materials shall not be applied at an individual user level, but rather at the library system or school district level.

It’s been a number of years since I have been in libraries, so my knowledge of databases isn’t what it once was. But given how many public schools and libraries have had access to entire digital repositories revoked over a single title complaint, I am curious if this a direct response to that extremism. Can companies meet these demands? Most digital resource providers sell on a packaged price model (i.e., you’ll get access to this package of materials at this cost, but if you pay more, you can then get this package). But perhaps this is also incentive for them to figure something out for fear of having no contracts at all in certain institutions.

Questions aside, that’s an excellent way of not blanket revoking access to crucial material.

As a citizen in a democracy, it is your duty to keep an eye on bills within your own state. Know when your state legislation is in session and have the contact information of your representatives handy. If you’re feeling really ambitious, have a few email templates ready to go that offer facts from research and statistics about the value and necessity of libraries that you can include in your correspondence relating to any bills coming up in your state.

You have the power to keep yourself informed not only about the future of these bills but about the bills that will inevitably emerge between January and May of 2025 at the state level. EveryLibrary has a regularly updated bill tracker you will want to check in on as part of your regular activism and educational work. Last year they also documented pro-library bills, so keep tabs to see if they continue for 2025.

Keep track of what’s happening in your own state as well. You can do that by regularly searching LegiScan by state and keyword (I use “library” and “librarian”). You may need to click through to ensure those bills are for the current legislative session and/or actually related to the topic of interest.

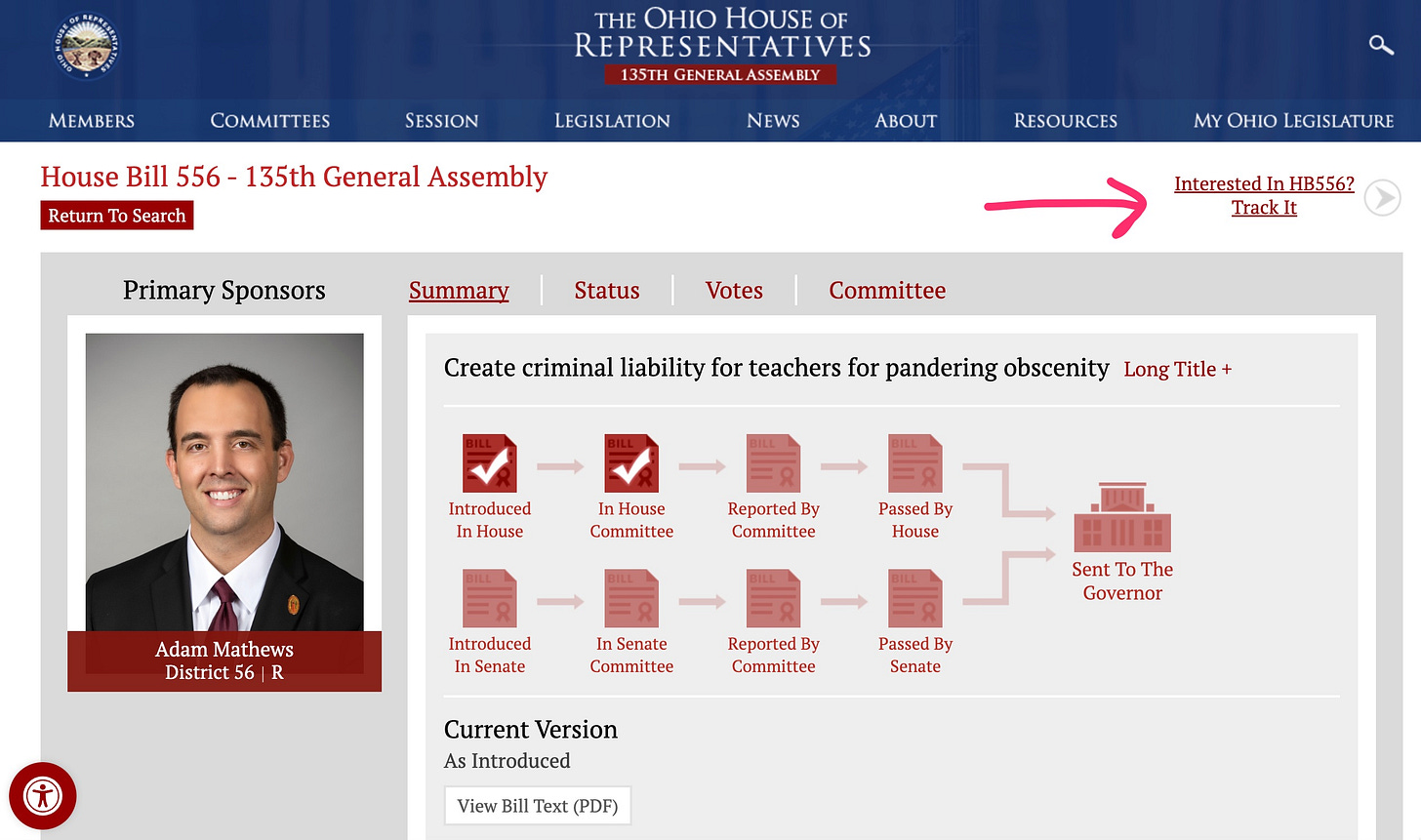

Many states have an option for you to set up an RSS feed to bills of interest. Here’s what it looks like on the Ohio House of Representatives website:

Other states share on their websites what tools are available to use. Here’s an example from the Iowa legislature with tons of options.

Depending on your job or your access to public or academic libraries, you may be able to find additional proprietary tracking software and apps.

Telling people where to find free books that have been banned is useless for solving the underlying issue here of intentional dismantling and destruction of public libraries and public school libraries. It’s sitting on the sidelines and pretending to have been involved in getting the job done. No matter how well intentioned, it’s not the solution here.

Showing up in board rooms, talking with those making these decisions is, and voting for local representation that cares about publicly funded democratic institutions of civic engagement that honor and defend the rights of every person within a community is.

Notes:

*It won’t. Kids in Illinois will have better access to accommodations than kids in neighboring Iowa or Indiana or Kentucky or Missouri.

**A felony, in many places, does not allow people to serve in certain public roles like on a school or library board and makes finding a job difficult. Meanwhile, it’s okay for felons to hold the role of president.

***My poorest selling book Body Talk: 37 Voices Explore Our Radical Anatomy features nude images of a wide range of bodies. Why do you think it pops up on challenge and ban lists? It’s the art, the fact that some of those bodies are not cis, and the essays in the collection don’t simply conform to a cishet white Christian able bodied idea of what anatomy should be. Plus, it’s too radical for teenagers who might think differently than their oppressive parents or guardians on these things.

+Michigan has only 10% of all their school libraries staffed by a full-time, certified librarian, which was subject of a failed bill last session. This, plus the reality that Michigan Library Association and the Michigan Association of School Librarians try not to tread on one another’s feet (which isn’t to say they don’t collaborate–they do!) might be why the aim of this bill is public libraries first.